dojo:

the primal School Blog

a place for writing and literature

that inspires the human soul

In 2016, I began my personalized, non-institutional poetry education by interviewing poets about one poem they had written and asking them about their craft, inspiration and creative process. Those interviews became a blog. But as so often happens with such endeavors, a season of growth came to an end and soon it was time to start another.

Three years of nomadic travel in the desert bloomed into poems of my own, which became a new book, and now also this new space on the web for anyone with a desire to plumb the depths of their life through poetry and other explorations of soul, meaning, and relationship.

The interviews you see here are as much about life as they are about books and literature…because literature is life.

PAUSE: Primal School Is Busy Rewilding

Friends and readers: thanks for all your support of Primal School and the written interviews I've been posting on here. With the help of friends and fellow poets I've been working to build a different kind of blog that continues to brings the best of poets' voices, but does so along with stories, lessons and other musings that will connect even more people with the power of poetry in these challenging times. I've been exploring the possibility of doing this via video or podcast, but the tactical and logistical wrangling and brainstorming have compelled me to hit pause on this for a while. If there's one thing I have learned in the last year from my various encounters in poetry, it's the willingness to be changed. And to be unafraid to initiate change. And to do so always in a spirit of openness and wonder.

The classroom is still here. I'll see you when I return. Thanks again for being my community. - Hannah

The Lessons of History, Re-Envisioning Our Language, and the Mysteries of Life and Death: Tod Marshall on His Poem "Birthday Poem"

Tod Marshall

Tod Marshall

I thought Primal School must be doing something right when I got an email from Washington State Poet Laureate Tod Marshall expressing his support for the blog and offering to connect. What I didn't expect was to receive an envelope in the mail about a week later with Range of the Possible, a compilation of Tod's own interviews with contemporary poets from Li-Young Lee to Yusef Komunyakaa. Generosity of this kind might very well be part of his incredibly full job description as the appointed ambassador of poetry in our home state. But when I wrote to him with some of my thoughts on the challenges facing poetry in our communities, his response, which startled me with its simplicity and is also captured in this interview, seemed to cut right through the fear and rancor and divisiveness facing our country to something far more essential. Even while noting fiercely (as he does here) the importance of understanding our present problems in historic terms, "I believe, truly believe, that art and kindness are why we exist," he wrote. Everything else, as they say, is technical. — HLJ

===

BIRTHDAY POEM

My mother turned 60 this week,

deep in that stretch where anything

can happen (her mother died at 57).

I'm 42, and Dante's dark forest, well,

let's just say it continues to thicken,

and I know what you spiritual people

are thinking, muttering koans under

your ginger tea breath: it can happen

anytime, anywhere, to anyone, and

that's why the moon doesn't cling

as it slides across the sky. Fine.

Last fall, hiking near Priest Lake,

I came across a teenage boy covered

with blood, sobbing. He held

a compound bow with pulleys

that looked like they could move the horizon

or at least hurl a razor-edged arrow

a couple hundred feet through the breast

and heart of a skinny doe and out again

and into the shoulder of a five-month fawn that

still quivered. Cedar scales

covered the forest floor, a mossy quilt

to hush the pain, and so we pulled

on the shaft, but it was stuck in bone,

and the fawn mewled, moaned, kicked

thin legs, black hooves like chips of coal.

I told the kid to find a big rock. Quick. He did

and held it toward me, somehow confused, and I

tried to smash the skull but missed once,

shattering the eye socket and breaking the jaw,

before ending the pain and walking away among massive trees

that held the sound in the harsh ridges of bark.

Jesus, Mom, I'd meant to write a Happy Birthday poem.

When I'd gone a hundred yards,

the quiet beneath the looming cedars

was the quiet I felt as a child in your arms.

You were a little bit older than that kid. This

is the best that I can do. Above the ancient grove,

tamaracks lit the hillside in an explosive gold

glowing toward dusk. Close your eyes.

You can see them. Keep them closed.

We'll all blow together and make a wish.

I thought Primal School must be doing something right when I got an email from Washington State Poet Laureate Tod Marshall expressing his support for the blog and offering to connect. What I didn't expect was to receive an envelope in the mail about a week later with Range of the Possible, a compilation of Tod's own interviews with contemporary poets from Li-Young Lee to Yusef Komunyakaa. Generosity of this kind might very well be part of his incredibly full job description as the appointed ambassador of poetry in our home state. But when I wrote to him with some of my thoughts on the challenges facing poetry in our communities, his response, which startled me with its simplicity and is also captured in this interview, seemed to cut right through the fear and rancor and divisiveness facing our country to something far more essential. Even while noting fiercely (as he does here) the importance of understanding our present problems in historic terms, "I believe, truly believe, that art and kindness are why we exist," he wrote. Everything else, as they say, is technical. — HLJ

===

BIRTHDAY POEM

My mother turned 60 this week,

deep in that stretch where anything

can happen (her mother died at 57).

I'm 42, and Dante's dark forest, well,

let's just say it continues to thicken,

and I know what you spiritual people

are thinking, muttering koans under

your ginger tea breath: it can happen

anytime, anywhere, to anyone, and

that's why the moon doesn't cling

as it slides across the sky. Fine.

Last fall, hiking near Priest Lake,

I came across a teenage boy covered

with blood, sobbing. He held

a compound bow with pulleys

that looked like they could move the horizon

or at least hurl a razor-edged arrow

a couple hundred feet through the breast

and heart of a skinny doe and out again

and into the shoulder of a five-month fawn that

still quivered. Cedar scales

covered the forest floor, a mossy quilt

to hush the pain, and so we pulled

on the shaft, but it was stuck in bone,

and the fawn mewled, moaned, kicked

thin legs, black hooves like chips of coal.

I told the kid to find a big rock. Quick. He did

and held it toward me, somehow confused, and I

tried to smash the skull but missed once,

shattering the eye socket and breaking the jaw,

before ending the pain and walking away among massive trees

that held the sound in the harsh ridges of bark.

Jesus, Mom, I'd meant to write a Happy Birthday poem.

When I'd gone a hundred yards,

the quiet beneath the looming cedars

was the quiet I felt as a child in your arms.

You were a little bit older than that kid. This

is the best that I can do. Above the ancient grove,

tamaracks lit the hillside in an explosive gold

glowing toward dusk. Close your eyes.

You can see them. Keep them closed.

We'll all blow together and make a wish.

===

A standout feature of this poem for me is its irony, beginning as a meditation on your mother turning 60 but then veering off into a reckoning with death, since birthdays are generally celebratory affairs. What began this poem for you?

It actually began as a sort of parody poem. I was thinking about poems such as William Stafford’s “Traveling Through the Dark,”Robert Wrigley’s “Highway 12, Just East of Paradise, Idaho,” and Marvin Bell’s “If Jane Were With Me”, or the “roadkill/mercy killing poem” and how the dynamics of all three of those poems might connect to masculinity. I think I might have written the deer killing moment first, and then stepped back and said, “Wait, what else is going on here?” I’m also very interested in critical moments of decision: the smaller choices we make and the crucibles on which those choices turn. The poem has numerous moments of choice — the decision to fire the arrow at the deer; the decision to have a child at a young age; the decision to bludgeon the fawn to death. Stafford’s poem, of course, is one of literature’s most haunting explorations of that inhabited moment of choice: “I thought hard for us all — my only swerving — / then pushed her over the edge into the river.”

Such decisions being moments where we can’t afford to “swerve.” I appreciated the tongue-in-cheek jab at New Age spiritualists in lines 6-11, giving the reader a glimpse into that Dantean consciousness you set up just before it. Seems a kind of rejection of the whole notion of peaceful non-attachment regarding death.

Well, that non-attachment is something I long for and dream of (which, of course, is exactly not how that non-attachment is brought about). I’m a hopelessly failed spiritualist and Zen practitioner. The world is too full of sharp teeth, I guess, and I’ve been bitten by them as well as bared my own at others more often than I care to admit.

Of course I can’t resist the urge to note that your name “Tod” is the German word for death.

Das ist Todt. Yup. The poem “Fuck Up,” a little later on in Bugle, is supposed to echo back to the death in “Birthday Poem.” From the moment we enter screaming into the world we’re already on our way to that whimpering exit. I just heard Tim O’Brien read at Gonzaga the other night, and he put it succinctly: “This is not a game with survivors.” But yes, imagistic echoes, proliferating motifs and echoey constructs throughout a book of poems are all of tremendous importance to me. It’s all there, from the substance abuse to information “leaking” to the life/death and creation/destruction dynamic. And at one point in the writing, I got the sense that the core of the book would revolve around the idea of how we construct myth/reify language in a post-apocalyptic setting. There are still traces of that in several of the poems — and I left them in there because that’s pretty much what we’re always up to. I just finished an amazing book by Victor Klemper; it’s one of those books that I’m embarrassed I didn't read earlier in life. It’s called The Language of the Third Reich. As a Jew living in Nazi Germany he was writing about the degradation of language; how words are drained of meaning or vampired (if that can be a verb) into empty vessels. To my mind, that degradation is the opposite of the work of poetry, and it’s unfortunately far too prevalent in the history of the last hundred years.

A kind evasiveness or lack of clarity perhaps, or doublespeak, if we were to take things Orwellian with that vampiring of the language. But returning us to your poem…some striking images from the hike at Priest Lake: the boy you encountered on the trail, the mortally wounded fawn, the “mossy quilt to hush the pain.” Did you give much thought to rhythm and meter at this poem’s writing? And how about the poem’s form?

Musicality in poetry is very important to me. So although I didn’t pursue any specific metrical shapes — unlike many of the other sonnets in Bugle, the book it appears in — I wanted to create a rich texture in terms of sound, especially during that moment of grotesquery. The poem starts out in a sort of chatty fashion and then builds to its music, I think.

Felt that in the reading. I’m interested in the mercy given to the fawn and how it becomes a kind of armature for the moving statement towards the poem’s end, by which time it’s addressed to your mother. The hint may be in those glowing tamaracks you end with, but I’m looking at the surprising lines, “You were a little bit older than that kid. This / is the best that I can do.” – what’s happening there?

Well I think that my initial impulse was to end on the violence, but I couldn’t think of how to do that, so instead I thought back to the frame of the poem — the figurative violence of how painful and challenging it must have been (as well as beautiful and fulfilling) for my mother to go from being a teenaged girl in high school to a woman responsible for another young life — I’m feeling this viscerally right now; this fall, my parents will celebrate their 50th anniversary, and I’ll be celebrating my 50th birthday. Anyhow, she must have felt heavily the chances of failure in protecting that young life, in spite of knowing she would give it her best. A terrifying transition in my mind. So I guess that’s how things tied together for me. “The best that I can do” — you can’t have any celebration of life without death lurking in the background — harkens toward the poem’s closure. The ending for me has always been very difficult to read (I’ve re-read the poem with my mother in the house and it’s hard not to lose it). Oh for the retreat to that sweet moment of unawareness nestled in your mother’s arms (however terrified every new mother must be).

Tod's process: "I love our woods and rivers and mountains, and I try to spend lots of time wandering around in them.

My fishing buddy Ryan Hardesty took this photo. I love how small I look behind the mid-stream rock,

upriver around a bend, wondering what might be there (a pursuit I suppose not terribly unlike the search for art)."

In your interview with Humanities Washington you described poetry’s ambiguity as being highly necessary in a culture that’s uncomfortable with mystery and not “having the answers.” How would you suggest that poets approach their writing and practice of poetry in uncertain times?

Well in the time since you put this question to me, the world has become much more uncomfortable and much more uncertain. Every day we see our President acting out in a manner ranging from indecorous to outlandish to completely barbaric. Any news which isn’t favorable to this administration is regarded as “fake news,” imperiling our freedom of the press. I could go on and on. It’s a horrific moment in history when such devastation, especially toward the most vulnerable members of our society, can be perpetrated by a kleptocratic plutocracy intent on…okay, I have to stop and take a breath to focus on your question. But first let me recommend Timothy Snyder’s book On Tyranny, a powerful little pamphlet that offers twenty ways to politically engage in times like this. All of his titles are excellent. I’m rarely ahead of the curve on things, but I bought On Tyranny when it first came out because I happened to be immersed in Snyder’s other writings. It’s since become a NYT bestseller, but I agree with what he says in the book, which is that it’s very important to get news from print sources. Web media can be okay, but the nature of the medium and its kinship with spectacle can make internet news much more prone to misinformation. It’s also important to practice corporeal politics: citizenship done right is getting our bodies out there and showing what we value.

Why such a focus on the news? Poetry is, of course, news that stays news. I think we should be reading widely in history and politics, philosophy and theology; we should all be trying to discover a “new” poet (new to each of us) every month and revel in that discovery for what it is: a new voice in one’s life. We should look to the work of poets in other cultures and and countries where the situation is historically more repressive than our own — Hikmet and Milosz and Akhmatova and Radnoti and so many others, as well as poets in our own tradition — June Jordan and Audre Lorde and Muriel Rukeyser — for whom social justice was a primary concern.

Anyhow, my main point is that the ambiguity, the grayness or confusion that is often stimulated by a poem or painting or sculpture, or any work of art — couldn’t be farther from the obfuscation that the Trump administration is engaged in. Poems invite us into mystery, into unknowing, and they do so in an attempt to enlarge our worlds rather than shrink them. As far as how poets approach their writing in “uncertain times” — I think that we have to look to the past both for the lessons that history can teach us about meglamaniacal authoritarianism, and how writers of the past have cultivated their art as a mode of resistance.

Thanks for the book rec – a timely and totally necessary read.On to standard questions: what advice would you offer to poets writing and practicing without the MFA/advanced writing degree? (Actually, one thing I’ve noticed is that there’s a lot of good general advice about how to improve one’s writing, but not much specific advice on how to revise a poem, so something along those lines would be very helpful).

Sure. I think that the hardest part of revision connects to the root of the word — to re-envision a poemis tough, especially once we get the poem typed out all pretty on the page. So, I delay that “typing out” step as long as possible. I try instead to rewrite the poem at least once by hand (shaping those words and scribbling out blunders, the routes that are perhaps too facile and easily drawn and aren’t the best for the poem). Once the poem is typed out it seems to become more fixed, static. Of course, lots of poets type their poems out on a computer or typewriter and make wonderful works; I just think that they need to be especially cautious of the poem “feeling done” before it actually is.

Another tidbit: be patient with the poem. I always try to let a few months go by before I transfer it from notebook (written by hand) to laptop (a typed version). I think that gives me some semblance of distance, which always helps the poem. More nuts and bolts: query each word, each adjective, each verb, each noun. Are they necessary? Are they precise? Musically integral? And the order that I’ve listed those three things are not necessarily an order of value — music probably supersedes all (to my thinking anyway).

If you could assign some “homework” to our online classroom of readers (it can be anything: a writing exercise, a craft book to read, a collection of poems to read, a link to an article).

How about something of all three: I love Jane Hirshfield’s work, and her book Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the Worldis a great new collection of essays on poetry. Robert Hass’s Twentieth Century Pleasuresmay be my all-time favorite. Also grooving on the poems of Jamaal May right now — he’s got a great voice with a powerful weave of image and music. Radnoti’s poems have also been on my mind a lot. I like to reread Adrienne Rich’s speech on “Claiming an Education” every few months.

And here’s an exercise, with thanks to Chris Howell: choose a language that you don’t know— French, Spanish, Greek, Slovene (it’s up to you but I’d avoid pictograph languages such as Chinese or Japanese). Then find the work of a famous poet writing in that language — if it’s French, then you could look at Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Nerval, or a host of other poets; it’s it’s Greek, then Cavafy, Seferis, Sappho, or something ancient; if it’s German, Rilke, Trakl. Choose one poem of 12-20 lines by the poet.DO NOT READ A TRANSLATION OF THE POEMinto English. Now, attempt to write a translation of that poem based solely on your reaction to the sound qualities of the original. Do this without looking up any words to translate. Instead you should try to follow syntactical patterns, formal constructs, and any other rhythmical devices that you feel relevant. The idea here is to use the imagination rather than the predeterminations of language logic, to let your mind loose from making sense of the original so you can see where the rhythms take you. After you’re complete (and ONLY after) you are done with your “translation,” you can have a look at at the English translation of the poem you’ve just worked with.

Staple together copies of the poem in the original language, your own “translation,” and the actual translation (three different poems).

For extra credit you can also turn in a translation of a poem from a language that you do know. Everyone MUST do the exercise above, but you can do an actual translation of another poem if you like (to boost your participation mark)!

An intimidating exercise which sounds incredibly fun. I’m going for it. Now tell us a poem you love, and tell us why you love it.

Robert Hass has been my favorite poet for a long, long time. I first read his poems in 1990, I think, and Praiseis a book to which I often return. There are anthology pieces in there, a delicious sense of sound, powerful poems on human frailty, philosophy, and the intersection of art and life. Human Wishes is equally wonderful, if maybe not quite as taut as a collection. Anyhow, the poem that I want to mention is “Faint Music.”It’s from Sun Under Wood, also a fine collection, and a virtuoso performance in syntax and sound. The poem is about grace and language and so many other things. I’m always a little stunned that Hass is so adept at translating haiku, and rendering devastating punchy images, as well as giving us sprawling poems in a wide range of voice such as this one.

Bonus question for Tod, per the poem’s last line and since your birthday's coming up: as a poet and human, tell us one wish.

That we get to redo the Presidential election? Or how about this: that each of us is able to tap into that highly poetic capacity to deeply listen to each other rather than to the propaganda of those who want to divide us.

===

TOD MARSHALLwas born in Buffalo, New York and grew up in Wichita, Kansas. He studied English and philosophy at Siena Heights University, holds an MFA from Eastern Washington University, and earned his PhD from The University of Kansas. Tod directs the writing concentration and coordinates the visiting writers series at Gonzaga University where he is the Robert K. and Ann J. Powers Endowed Professor in the Humanities. He enjoys backpacking and fishing and spends about a month of every year out of a tent. He currently serves as the 2016-2018 Washington State Poet Laureate. You can keep up with him on Twitter: @wapoetlaureate

Experience and The Imagination, Metaphor as Survival, and Healthy States of Flow: Patricia Colleen Murphy on Her Poem "How The Body Moves"

Patricia Colleen Murphy

Patricia Colleen Murphy

If genuine healing from a difficult and traumatic past takes place in the soul and subconscious (and not the support of the world around us), it would seem that Patricia Colleen Murphy has dedicated her path in poetry to exactly that, lifting others up the whole way. The founding editor of Superstition Review at Arizona State University won the May Swenson Poetry Award for her book Hemming Flames, a copy of which she sent to me on my request. I was opened completely by the book's rawness, an admixture of crushingly difficult memories paired with the complexities of hard-won wisdom. Here is a poet moving personal and confessional writing forward with unflinching earnestness, all the while nurturing and promoting writers into their own humanity and resilience. In every way she strikes me as such a model for writers, from her poem's empathic resonances to the way she lives her life. — HLJ

===

Melanie, the Siamese,

on the front porch with baby me.

In pictures, the two of us

are almost the same size.

Later my mother

bought Persians, bred them,

used the money for jewelry,

cigarettes, Drambouie.

The first time a litter came

she sent me searching the house

to find and clean the afterbirth.

I found the babies limp,

smothered in their sleep.

Only twenty more miles.

I am 15. My uncle is driving.

My mother has fled again in her

Oldsmobile, heading for Palo Alto.

We were fighting. She took

all the pills she could find.

My uncle sighs, repeats that

his mother died giving birth to him.

One tenth her weight, he came

screaming from her pelvis on the

coldest Minnesota day in history.

The freeway slips under us like night.

From here I think the hills are

impoverished sisters huddled for warmth

under green mohair blankets.

Seventeen of them: stomach to knee,

buttock to backbone.

We glide past their ankles.

Once I dreamt I was nine months pregnant.

When I went to the bathroom

the baby slipped out like a miraculous

bowel movement. She had blond hair,

and a T-shirt that said French Countryside.

A neighbor saw the birth through the window.

He smiled, continued mowing the back field,

and I hung a bell.

Patricia Colleen Murphy

If genuine healing from a difficult and traumatic past takes place in the soul and subconscious (and not the support of the world around us), it would seem that Patricia Colleen Murphy has dedicated her path in poetry to exactly that, lifting others up the whole way. The founding editor of Superstition Review at Arizona State University won the May Swenson Poetry Award for her book Hemming Flames, a copy of which she sent to me on my request. I was opened completely by the book's rawness, an admixture of crushingly difficult memories paired with the complexities of hard-won wisdom. Here is a poet moving personal and confessional writing forward with unflinching earnestness, all the while nurturing and promoting writers into their own humanity and resilience. In every way she strikes me as such a model for writers, from her poem's empathic resonances to the way she lives her life. — HLJ

===

HOW THE BODY MOVES

Melanie, the Siamese,

on the front porch with baby me.

In pictures, the two of us

are almost the same size.

Later my mother

bought Persians, bred them,

used the money for jewelry,

cigarettes, Drambouie.

The first time a litter came

she sent me searching the house

to find and clean the afterbirth.

I found the babies limp,

smothered in their sleep.

Only twenty more miles.

I am 15. My uncle is driving.

My mother has fled again in her

Oldsmobile, heading for Palo Alto.

We were fighting. She took

all the pills she could find.

My uncle sighs, repeats that

his mother died giving birth to him.

One tenth her weight, he came

screaming from her pelvis on the

coldest Minnesota day in history.

The freeway slips under us like night.

From here I think the hills are

impoverished sisters huddled for warmth

under green mohair blankets.

Seventeen of them: stomach to knee,

buttock to backbone.

We glide past their ankles.

Once I dreamt I was nine months pregnant.

When I went to the bathroom

the baby slipped out like a miraculous

bowel movement. She had blond hair,

and a T-shirt that said French Countryside.

A neighbor saw the birth through the window.

He smiled, continued mowing the back field,

and I hung a bell.

===

A bit of a confession to start us off; I wanted to discuss this poem partly for selfish reasons: reading HEMMING FLAMES was a deeply relational experience for me, as someone who grew up with domestic violence and also had a tough relationship with her mother. This poem stood out to me because it seems to be reckoning with other themes such as aging and death. What began it for you?

Thanks for sharing that with me. It's meaningful to hear how others are affected by the work. I am going to admit to you that I wrote this poem 20 years ago, as part of my MFA thesis in 1996. So this poem started when I was in my early twenties trying to come to terms with my estrangement from my mother. You'll note it has perhaps a more tender, contemplative tone than others in the collection; perhaps more hopeful even.

At the time I wrote it my mother was still alive but I had not spoken to her for a long time. It was necessary but sad to keep that distance. The estrangement lasted about eight years.

I hope it isn't too challenging to discuss a poem you wrote such a long while ago. Perhaps tell us a bit about the poem’s title and how you came to it. The piece on its face doesn’t seem only to be about movement per se, the way a body for instance moves through space (“Only twenty more miles…”), and it seems there’s a different kind of movement happening here. Is there some other change in the reader or speaker that you intended in writing this?

It's refreshing to look at the old work, so thank you. The title, like a lot of phrases in the book, is meant to be ironic. These are bodies that are not moving, really. They are stagnant. They are desperate. They are acted upon instead of acting. Even in motion they are motionless. So the title could also be "How the Body Does Not Move." But I wanted that tension between the directive “How” and the aimlessness in the poem. I remember my mentor Beckian Fritz Goldberg commenting that many of my titles start with the word "How," which is a little joke I play, as a way of pretending there’s agency where there is none.

And yes living with my mother meant constantly searching. Oh my goodness, and also constantly acting. Right now I’m reading The Tao of Humiliation by Lee Upton and just highlighted the line, “By the time I was thirteen I learned to smile often—to reassure my mother that I wasn’t being harmed by her sadness.”

Adding that to my list. I'm caught by this idea of agency as illusion, something that we cling to in the vast game of pretend/hide-and-go-seek that happens in families rocked by trauma or abuse. The enactment of that denial in a poem is a bit of a feat.

I like your phrase "enactment of denial." Denial is hard to write because if its layers. And perhaps that's a reason it took me so long to finish this book. There is the quotidian image hovering just over the traumatic image. And how to balance them so that the work is neither maudlin nor solipsistic? That is really hard. I had a lot of false starts that were surely both.

Every wounded child is also the "victim of a victim," and I appreciated that your collection as a whole explores that side of the relationship with your mother as well. Your work is characterized as surreal – I work with surrealism in my own writing, and the struggle is how to go there without turning silly or otherwise expelling the reader from the poem. Here you’ve got the hills over the highway turning into “impoverished sisters” huddled under “green mohair blankets”, and a deeply mysterious birth image at the end. What was happening for you there?

Ah you make good points about surrealism turning either silly or inaccessible. Poets cut their teeth on those mistakes! I know I did. In this poem and in this book, the surrealism is synonymous with the escapism it took to survive. It's the same imagination it takes to live through something you don't think you'll get through.

I have a line in another poem in this book, "misting the ferns with a mental mister," and that's the best explanation I can give you about how these surrealist flourishes work in the poems. It's coping through metaphor. Through imagination. Through being someone and somewhere else.

So well said; I'm just looking at that poem again and noting the denialism inherent in the title there too, Magritte’s image of that famous pipe with the line "This Is Not a Pipe." I also want to dig a little deeper there on how you cut your teeth -- was it just through practice and trial and error, or did you have models?

Yes, I forgot the title that started the poem just now when I quoted that line, but it's a perfect example. Magritte's title for that painting is "The Treachery of Images." We can apply that to the surrealism in my work, if you like. I may be showing you something, but it's simply an image and not the experience itself. You'll need to figure out what it means to you, how it relates to your life.

I did have models. I keep a reading journal where I gather a lot of moments that affected me deeply, and I study the journal before I compose to get into that headspace.

I should also say I have an undergraduate degree in French, so I have read so many of the French surrealists in the original and that’s becomes one of my ways of seeing and speaking.

And then there are some clear American influences as well: James Tate, Russell Edson, Charles Simic; Beckian of course. And Marianne Boruch.

There was also a lot of trial and error!

That representative approach is a tough pill to swallow for the literalists out there, but it's something I try to remind myself when I'm showing up to a poem I can't grasp with my reason alone, that there is a world beyond this world that the poet is inviting me to enter with my own set of experiences and memories.

I heard Terrance Hayes say "I keep one foot in experience and one in imagination."

Perfect.

Yes he is. [Laughter]

You’ve spoken elsewhere of John Berryman’s influence, whose story is familiar to many. And it seems you’ve grappled with the worst darknesses of the psyche, some of which seem unimaginable (I'm thinking of the younger Trish having to parent herself and rescue her mother from repeated suicide attempts). Children inherit those wounds from their parents and then have to find ways to carry them if not heal from them. What role if any has poetry played in that process for you?

Well the Hayes quote helps me answer that! Poetry lets me straddle reality and fantasy (and when I say fantasy, for me it really means the ideal life I wish I’d had). It has allowed me to do that in two ways, reading and writing. I was writing and publishing poems about my family starting in middle school. It helped me process what was happening. And reading always helped me too, not just for the escapism it provided but also for the intellectual stimulation and the "break" from my own thoughts.

I think about the concept of "flow" and how helpful it is to be there. I think that's a state that people are trying to enter in all kinds of ways (healthy or unhealthy), and I'm lucky that I like to enter flow through either language or exercise. I can totally lose myself for hours at a time when I write, read, run, ride, or swim.

What a true blessing to not have to be needed in impossible ways. What a thrill to be in a positive headspace.

"This is the Gila Trail at South Mountain Park, where I like to run and play."

"These are my three Vizslas. Penny is 9, Rooster is 11, and Nutmeg is 6 months."

I read a lot of Jungian depth psychology – James Hillman, James Hollis – and it strikes me just how easy it is, in the quest to reclaim one's selfhood from deep wounds, to descend into those unhealthy patterns you mentioned like addiction or other forms of escape. The only way to break from our old lives and stories, of course, is to opt for new ones entirely, which with the help of art it seems you've done.

I like that phrase, "quest to reclaim selfhood." And I think about people who ask about the confessional nature of the book, asking, "Were you afraid what your family would think?" And I respond with, "Were they afraid what I would think when they were making selfish choices?"

I mean there was some extremely bad behavior – and oh, lots of gaslighting. If I've tried to break from my own early life, it's by being transparent and honest and helpful and empathetic.

Though I will say to you that I come from a place of huge privilege. Everyone in my family had a genius level IQ. My mom graduated from Stanford with degrees in Political Science and International Relations in 1961. We had smart conversations in the home; that is, when we weren't begging folks to take their meds.

How such suffering can still be steeped in privilege is something I think much of our current discourse tends to ignore with its focus privilege as a racialized white monolith. The gaslighting that's prevalent in families also seems to be showing up a lot in the wider culture these days. Poetry and art are perhaps just one means of bringing that compassion and empathy you describe.

Onward to standard questions: Could you give us three things a writer can do, on a daily or weekly basis, to educate themselves on craft in a manner comparable to an MFA education?

Form a writer’s group. Whether it’s online or in person, sharing your work with others can be motivational and can help you create and revise.

Read and review books. You can keep a word document with these reviews if you don’t want to share them, but other authors really appreciate reviews on Goodreads or Amazon. Be a good literary citizen and share your thoughts on contemporary writing.

Reach out to established poets. If you read a book or a poem in a journal that moves you, email the author and let them know.

Do you have any homework to assign our readers?

Yes, here's some homework: an exercise I call FIVE WAYS.

I have many revision “games” to play with poems. I do this after a poem has existed for a while, and it’s time to make sure it’s as good as it can me. For the FIVE WAYS activity, take a poem that has been in the drawer for a while. First, remove the line breaks in your poem so that it reads as one big paragraph. Then put the line breaks back in FIVE WAYS. Does you poem want to be in couplets? In all one stanza? Does it like enjambment? End-stopped lines? Let your poem tell you what it needs by rearranging and re-reading and re-seeing it in five different ways.

Share a poem you love with our readers and tell us why you love it.

I love Daniel Borzutzky’s "The Broken Testimony", from his collection The Performance of Becoming Human. He manages to be political and personal, predicting "the best dictators don't kill their subjects rather they make their subjects kill each other." It’s a great study in both composition and form that invites the reader to write and to scavenge.

===

Patricia Colleen Murphy founded Superstition Review at Arizona State University, where she teaches creative writing and magazine production. Her book Hemming Flames (Utah State University Press, 2016) won the May Swenson Poetry Award judged by Stephen Dunn. A chapter from her memoir in progress was published as a chapbook by New Orleans Review. Her writing has appeared in many literary journals, including The Iowa Review, Quarterly West, and American Poetry Review, and most recently in Black Warrior Review, North American Review, Smartish Pace, Burnside Review, Poetry Northwest, Third Coast, Hobart, decomP, Midway Journal, Armchair/Shotgun, and Natural Bridge. She lives in Phoenix, AZ.

The Definition of Home, Keeping the Poem In the Poem, and Knowing What Moves You: Keegan Lester on His Poem “A Topography of This Place”

Keegan Lester

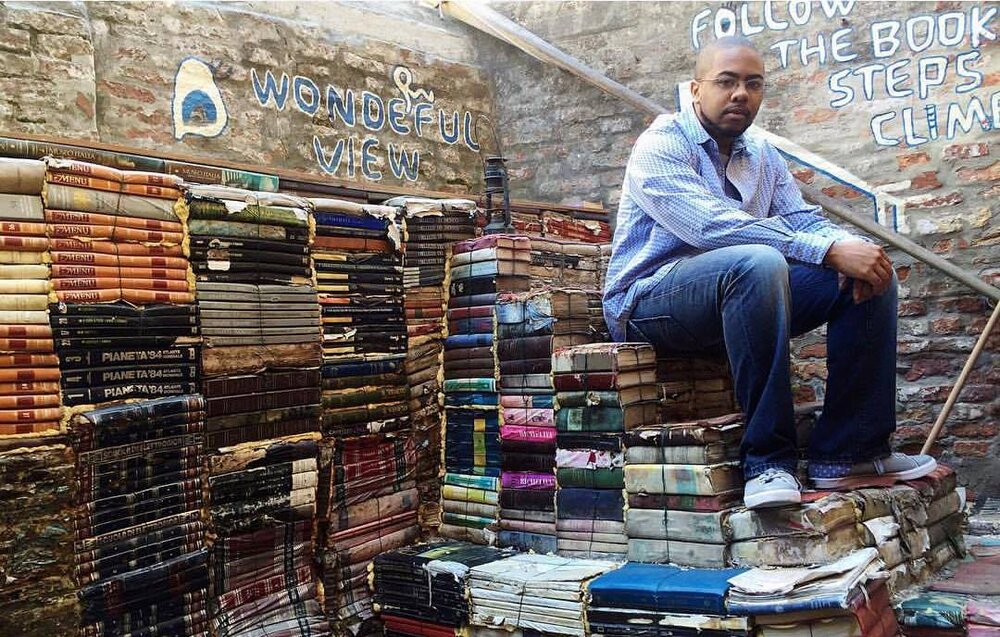

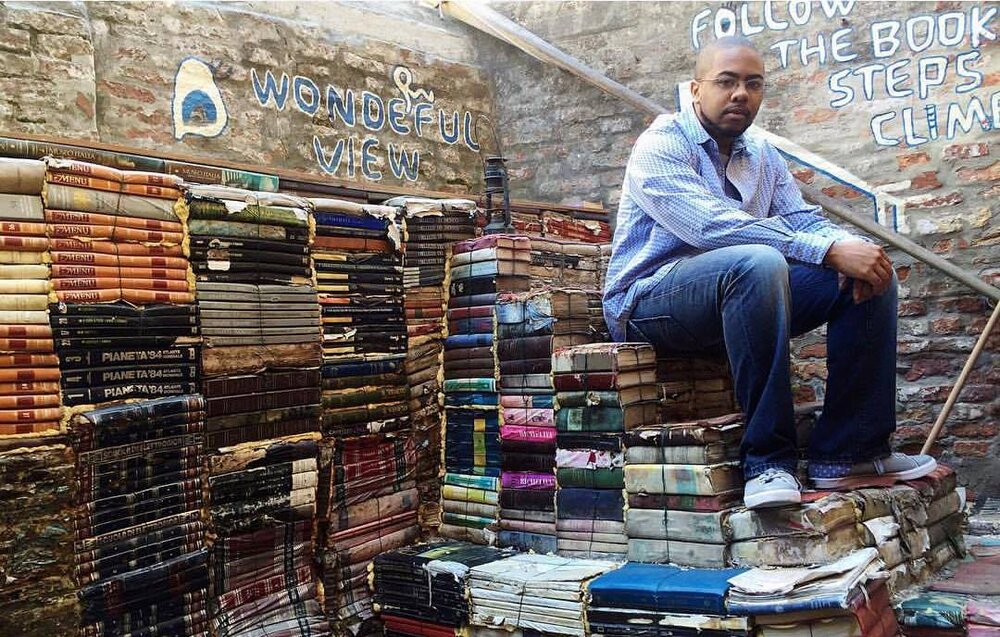

Keegan LesterThe first time I ever met Keegan Lester I was a daunted rural visitor to New York in the crushing heat of a mid-July. The impromptu tour he gave me of his favorite haunts near Columbia University (his MFA alma mater), was an unexpected gift – and the introduction to a poet whose work, perhaps more than that of any poet I’d met, mirrors his character: fierce in its insistence on gentleness, conscientious through its softspokenness, and present and alive to the world. These things made me all the gladder that Keegan’s first book of poems, this shouldn’t be beautiful but it was & it was all I had, so I drew it, had recently won the Slope Editions Book Prize ( available for pre-order here and due for release in the coming month). In the spirit of the new year and with Keegan’s encouragement, I’m introducing multimedia to the Primal School blog with these videos he recorded. In them he discusses his love of home as an idea as well as a place we choose -- the notion that “home”, no matter how small, can be a conduit for storytelling, for sharing, and for exploring those sadnesses, elations and struggles which make people more aware of their alikeness in a time of bitter polarization and difference. I personally feel lucky to have been a recipient of his “ocean’s newfound kindness.” – HLJ

===

so the sailors went home.

No one jumped from cliffs anymore.

People stopped painting and photographing the ocean

because the sentiment felt too close to a Hallmark card.

Everyone had treasure because

it was easy to find,

thus the stock market crashed.

Then the housing bubble burst

mostly not due to the ocean,

though one could speculate pirates

were going out of business and defaulting on loans.

When I say speculate, I mean I was reading

the small words that crawl at the bottom

of the newscast, but I was only half paying attention

because Erin Burnett was speaking

and she’s the most real part of this poem.

I’m speaking in metaphor of course.

The end of the world is coming

seagulls whispered to the fish

they could not eat due to their fear

of the ocean’s newfound kindness.

One of my professors spoke today.

She hates personification, treasure and linear meaning.

She hates poems not written by dead people.

She hates the ocean’s newfound kindness,

she wrote it on my poem.

Not everything can be ghosts and pirates, she says.

But that’s why I live here.

My rhododendron has never crumpled in the summer.

Keegan Lester

Keegan LesterThe first time I ever met Keegan Lester I was a daunted rural visitor to New York in the crushing heat of a mid-July. The impromptu tour he gave me of his favorite haunts near Columbia University (his MFA alma mater), was an unexpected gift – and the introduction to a poet whose work, perhaps more than that of any poet I’d met, mirrors his character: fierce in its insistence on gentleness, conscientious through its softspokenness, and present and alive to the world. These things made me all the gladder that Keegan’s first book of poems, this shouldn’t be beautiful but it was & it was all I had, so I drew it, had recently won the Slope Editions Book Prize ( available for pre-order here and due for release in the coming month). In the spirit of the new year and with Keegan’s encouragement, I’m introducing multimedia to the Primal School blog with these videos he recorded. In them he discusses his love of home as an idea as well as a place we choose -- the notion that “home”, no matter how small, can be a conduit for storytelling, for sharing, and for exploring those sadnesses, elations and struggles which make people more aware of their alikeness in a time of bitter polarization and difference. I personally feel lucky to have been a recipient of his “ocean’s newfound kindness.” – HLJ

===

so the sailors went home.

No one jumped from cliffs anymore.

People stopped painting and photographing the ocean

because the sentiment felt too close to a Hallmark card.

Everyone had treasure because

it was easy to find,

thus the stock market crashed.

Then the housing bubble burst

mostly not due to the ocean,

though one could speculate pirates

were going out of business and defaulting on loans.

When I say speculate, I mean I was reading

the small words that crawl at the bottom

of the newscast, but I was only half paying attention

because Erin Burnett was speaking

and she’s the most real part of this poem.

I’m speaking in metaphor of course.

The end of the world is coming

seagulls whispered to the fish

they could not eat due to their fear

of the ocean’s newfound kindness.

One of my professors spoke today.

She hates personification, treasure and linear meaning.

She hates poems not written by dead people.

She hates the ocean’s newfound kindness,

she wrote it on my poem.

Not everything can be ghosts and pirates, she says.

But that’s why I live here.

My rhododendron has never crumpled in the summer.

This poem seems especially relevant in our present cultural moment. Tell us what began it.

"It's a love poem to West Virginia..." Why it's important to entertain and write for others, and drop your ego from your work.

---

“Don’t revise the poem out of the poem.”

---

In your view, what purpose does poetry serve in the world?

A poem here is an attempt by the writer to understand something...then be a force of its own in the world which can preserve family stories and collapse false or misleading cultural narratives.

---

What advice would you offer to poets writing and practicing without the MFA/advanced writing degree?

“Find what you love, something that catches your eye and moves you, and then do it…do it every day, and know that it’s going to take time to get to where you want.”

---

Write a persona poem that draws from a place as far outside of your experience as possible then see what happens.

---

Tell us just one poem you love, and why you love it.

Here are three:

The first time I heard Nikki Giovanni reading "Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea (We're Going to Mars)” in a non-fiction class in undergrad, I knew instantly that I wanted to do what she was doing in that poem. Prior to that I didn’t know that contemporary poetry could be capable of such power. I enrolled in a poetry class after that and never looked back.

Jason Bredle’s poem "On the Way to the 53-B District Court of Livingston County, October 1, 1999” was a huge turning point in my poetry. I remember being in my thesis meeting and telling my advisors, “I didn’t know you were allowed to write like this.” This poem, from his book Standing in Line for the Beast, helped me see that in poetry there’s nothing that isn’t allowed. We can write our own rules so long as the poem moves someone.

In my opinion Richard Siken’s “Scheherazade” from his collection Crush is the most perfect love poem ever written. The entire collection is brilliant and extremely helpful for poets looking to expand their poetry skills, especially in regards to pacing, use of white space, prosody, and just working with images at the line level.

Give us an image of something that creatively inspires you.

Keegan's poetic inspiration: his best friends, Crich and Courtney.

Keegan's poetic inspiration: his best friends, Crich and Courtney.

These are two of my closest friends in the world, Crich and Courtney, in Crich’s living room in Morgantown, West Virginia. Lex, the gigantic puppy, is on the sofa.

When I’m in town I always help Crich walk Lex around a gorgeous neighborhood called South Park, discussing house design and other topics as we go. Crich has broken so many intellectual and aesthetic barriers for me, helping me see the world more clearly, most especially through film and design. I've taught him about contemporary poetry and we’ve been close friends for over a decade. We talk to each other in a language that I don't use with anyone else, unfortunately, which can be a lonely space to occupy. I think I often go to that place in my writing. So much of this room is where I live in my head.

In this photo there are many of these high aesthetic moves in evidence, from the Cunard poster in the background to the Sheraton Sofa to Crich’s Billy Reid sweater. None of it is pretentious. And each one has some kind of a cut-back to a story or revelation for me, some kind of vital experience. The sofa for instance was originally Crich’s grandmother’s, and it was in her house, and he brought it with him all the way from Louisiana. And he has this wonderful picture of the two of them, I believe in his dining room, sitting in that couch.

===

Keegan Lester is the winner of the 2016 Slope Editions Book Prize, selected by Mary Ruefle, for his collection this shouldn’t be beautiful but it was & it was all i had, so i drew it. He is an American poet splitting time between New York City and Morgantown, West Virginia. His work is published in or forthcoming from Boston Review, Atlas Review, Powder Keg, BOAAT, The Journal, Phantom, Tinderbox, CutBank, and Sixth Finch, among others, and has been featured on NPR, The New School Writing Blog, and Coldfront. He is the co-founder and poetry editor for the journal Souvenir Lit. You can follow him on Twitter @keeganmlester or on Instagram @kml2157. His book is currently available for preorder here.

Standards of Beauty, Decolonizing Our Language, and Poetry as a Dialogue With Our Contemporaries: Katelyn Durst on Her Poem "Curl"

Katelyn DurstIn this season of tumult and deep psychic unrest for our country, it hardly seems a coincidence that I'd been pondering bringing in new interviews with poets whose work is inseparable from their activism. Incidentally I'd also been aiming to feature younger voices. By the time of our interview, Katelyn Durst had impressed me not just with her poems of struggle and identity and longing and resilience, but her highly visible and participatory commitment to the social justice that inflames her writing. From a distance of months – I'd interviewed Katelyn back in August – it occured to me while putting together this post that "Curl" is not merely a poem about race or identity, but love. Self-love of the kind Katelyn embodies here, a kind that is so easy to forget in times such as this: just one gift of the many which poets can offer as utterances of comfort in a hurting world. – HLJ

===

So you and I first met at Grunewald Guild back in May, and I was sitting with you in the lounge area by the kitchen, and you read me this poem and I remember thinking, “this girl is fearless.” Tell me a bit about this piece – what began it for you and how you wrote it.

It’s so great to hear that, because the truth is I often feel afraid. This poem came out of a homework assignment that was given to an international baccalaureate (IB) 11th grade English class I was TA-ing for this school year. The teacher assigned the poem "Girl" by Jamaica Kincaid, and the poem really resonated with me, with its fractured repetition. If there’s one thing people talk to me a lot about, it’s my hair. So I went home and wrote down the things I remembered people saying to me about it – as it turns out, they were overwhelmingly negative and hurtful things – and wrote them verbatim into what eventually became this poem.

===

CURL

Straighten your hair just once. Blow dry it or somethin’ and it will be down to your shoulders. Fix your hair. Tie back your hair. Wear a hat over your hair. I knew that was you because of your big hair. Your hair looks like the Medusa’s snakes. Why do you have just one dread lock? Can you go back and look in the mirror. Sit still while I’m braiding your hair. Sit in this chair so I can see the top of your head. Sit outside so that your hair doesn’t get all over the kitchen floor. How do you make black hair look so nice? You should straighten it. Texturize it. Don’t brush it. Brush it with just your brown fingers. You need to buy an actual brush and a comb. Your hair is so dry it would soak up a whole tub of moisturizer. Your hair is so big. Wow, your hair is so beautiful. Can I touch your hair? Have you ever washed your hair? Is that your real hair? Can you do that to my hair? You should straighten your hair. The back of your head is a kitchen. Twist out your hair by sectioning out single sections and twisting small parts of hair together, like a two-strand braid. Make the twists stretch around your head andwear a silk cap at night to help your kitchen from getting poof or static. Long bouncy curls are cute. I saw a guy who had hair like you, so I assumed he was homeless. Men don’t like curls; they don’t want their hands to get stuck when they run their fingers in your hair. Straighten your hair. Natural is the new black, get your weave here. Put flowers in your hair. This hay will never come out of your hair. You have paint in your hair. That braid makes you look like Pocahontas. Cornrows make you look like a boy. Long braids and gym shorts make you look like a boy. Put curlers in your hair to get a more succinct pattern. Bantu knots. Sculpted Afro. Jerry curls. Did you wake up like that? The less black you look, the less likely you are to questioned by police. Don’t put wool hats on your hair, it will mess up your kitchen. How to get your most defined Wash N Go. How to make DIY Clay Wash. How to make natural, black, curly hair look elegant: Pin it up. What’s wrong with your hair? Why does your hair stick up like that? Your hair looks like a lion’s mane. Are you from Africa? Are you from India? What are you? You look like you just got here. I can’t wait to get home and see your beautiful curls...Daddy. Here is a link to several different wigs you should try. It will make you look much prettier. Straighten your hair. Just get your hair wet so it doesn’t look so dry. Is that a stick in your hair? Do you have green beetles in your hair like Bob Marley did? What kind of hairstyle is that? The straighter your hair, the more likely you are to succeed. So, just sit still. Let this heat press away your curls, your kitchen, your blackness. Let it warm you like the love you are sure to soon have.

Katelyn DurstIn this season of tumult and deep psychic unrest for our country, it hardly seems a coincidence that I'd been pondering bringing in new interviews with poets whose work is inseparable from their activism. Incidentally I'd also been aiming to feature younger voices. By the time of our interview, Katelyn Durst had impressed me not just with her poems of struggle and identity and longing and resilience, but her highly visible and participatory commitment to the social justice that inflames her writing. From a distance of months – I'd interviewed Katelyn back in August – it occured to me while putting together this post that "Curl" is not merely a poem about race or identity, but love. Self-love of the kind Katelyn embodies here, a kind that is so easy to forget in times such as this: just one gift of the many which poets can offer as utterances of comfort in a hurting world. – HLJ

===

So you and I first met at Grunewald Guild back in May, and I was sitting with you in the lounge area by the kitchen, and you read me this poem and I remember thinking, “this girl is fearless.” Tell me a bit about this piece – what began it for you and how you wrote it.

It’s so great to hear that, because the truth is I often feel afraid. This poem came out of a homework assignment that was given to an international baccalaureate (IB) 11th grade English class I was TA-ing for this school year. The teacher assigned the poem "Girl" by Jamaica Kincaid, and the poem really resonated with me, with its fractured repetition. If there’s one thing people talk to me a lot about, it’s my hair. So I went home and wrote down the things I remembered people saying to me about it – as it turns out, they were overwhelmingly negative and hurtful things – and wrote them verbatim into what eventually became this poem.

===

CURL

Straighten your hair just once. Blow dry it or somethin’ and it will be down to your shoulders. Fix your hair. Tie back your hair. Wear a hat over your hair. I knew that was you because of your big hair. Your hair looks like the Medusa’s snakes. Why do you have just one dread lock? Can you go back and look in the mirror. Sit still while I’m braiding your hair. Sit in this chair so I can see the top of your head. Sit outside so that your hair doesn’t get all over the kitchen floor. How do you make black hair look so nice? You should straighten it. Texturize it. Don’t brush it. Brush it with just your brown fingers. You need to buy an actual brush and a comb. Your hair is so dry it would soak up a whole tub of moisturizer. Your hair is so big. Wow, your hair is so beautiful. Can I touch your hair? Have you ever washed your hair? Is that your real hair? Can you do that to my hair? You should straighten your hair. The back of your head is a kitchen. Twist out your hair by sectioning out single sections and twisting small parts of hair together, like a two-strand braid. Make the twists stretch around your head andwear a silk cap at night to help your kitchen from getting poof or static. Long bouncy curls are cute. I saw a guy who had hair like you, so I assumed he was homeless. Men don’t like curls; they don’t want their hands to get stuck when they run their fingers in your hair. Straighten your hair. Natural is the new black, get your weave here. Put flowers in your hair. This hay will never come out of your hair. You have paint in your hair. That braid makes you look like Pocahontas. Cornrows make you look like a boy. Long braids and gym shorts make you look like a boy. Put curlers in your hair to get a more succinct pattern. Bantu knots. Sculpted Afro. Jerry curls. Did you wake up like that? The less black you look, the less likely you are to questioned by police. Don’t put wool hats on your hair, it will mess up your kitchen. How to get your most defined Wash N Go. How to make DIY Clay Wash. How to make natural, black, curly hair look elegant: Pin it up. What’s wrong with your hair? Why does your hair stick up like that? Your hair looks like a lion’s mane. Are you from Africa? Are you from India? What are you? You look like you just got here. I can’t wait to get home and see your beautiful curls...Daddy. Here is a link to several different wigs you should try. It will make you look much prettier. Straighten your hair. Just get your hair wet so it doesn’t look so dry. Is that a stick in your hair? Do you have green beetles in your hair like Bob Marley did? What kind of hairstyle is that? The straighter your hair, the more likely you are to succeed. So, just sit still. Let this heat press away your curls, your kitchen, your blackness. Let it warm you like the love you are sure to soon have.

===

It’s funny that you mention Kincaid, as a friend just gave me a copy of her book A Small Place, and Kincaid has been on my mind. "Curl" is a longer poem and has an almost obsessive quality to it. Since there’s no other way to say it: that’s a lot of hurtful statements. What’s more is that it strikes me that not all the statements are negative on their face.

I love A Small Place and got to explore misplaced identities in Kincaid’s writing, and so she’s played a pretty significant role on my development as a writer.

With “Curl”, I wanted a longer piece that built on itself into a kind of litany of words and phrases that emphasize the ludicrousness and hurtfulness of some of the things people have said to me in the past. While writing it I realized I was also touching on how those things are bound up with our culture’s consumerism and its unreasonable standards of beauty. For me, race is always going to enter the picture, a black woman who keeps her hair natural and gets constant criticism or input on how she should wear it. Though it’s not all negative statements that I remember: the note from my dad was something I’d found as an adult in a baby box my parents saved, and it really struck my heart and I’ve carried with me. In writing this poem I had to include some positive things as well, because I wanted to remind myself and my readers that the loving and supportive things people say to us and which make us feel valued and beautiful are worth their weight in gold. We should never forget them.

I’m loving that play of contrasts, and how this poem has multiple speakers in it even as it builds thematically into an interrogation of identity and belonging. There's that word “microagression”, the term we use for statements directed at people of color that aren’t malicious but are still hurtful.

It’s nothing other than a microaggression to have people say things like “May I touch your hair”, “Could you do that to my hair”, “Is that your real hair”, or “What hairstyle is that?”

And of course having someone just reach out and touch your hair is a deep wounding for so many blacks. Back in high school I remember watching this documentary called Cold Water, and there was a scene in it where two young women (both women of color) were discussing the affection and connection inherent in the gesture of playing with someone’s hair. But there’s this other story around the touching of hair as a kind of violation. With this poem I feel as if you’re speaking to both those truths, as if you’re arguing with yourself.

I’ve never seen Cold Water, but it sounds interesting – there's definitely a disconnect between touching someone's hair out of earned intimacy or affection versus touching someone's hair because you can't believe it's real or you’re simply curious what it feels like. It's the difference in loving and exoticizing. On the one hand you have someone touching you out of regard and tenderness, and on the other someone who has no connection with you just wants to touch your hair because it's a strange new fruit. It’s almost like at the zoo where there are signs that say not to feed the animals but people do it anyway.

Wow, what an analogy. Worse than a museum artifact.

A notable feature of this poem is its absence of line breaks; you just poured the length of it into one long paragraph. Was that its original form?

That was its original form. And I must say that my other poem, "Girl”, was written as a prose poem also – I just felt it was the appropriate form for this piece. I was interested in bringing home the full scope of these different statements, presenting them in a way that was perhaps a bit “anti-poem”, that is, really having others read the poem without line breaks or anything fancy and to take the words unfiltered and for what they are. I didn't really feel that this poem had enough connection to "Girl" to warrant a response to Jamaica Kincaid's own “Girl", though I may do that in the future. I’ve recently read the “mirror poems” of Sharon Olds and other poets, where they write a poem as a response to another poet. I really like that idea because it reminds me how our work is an ongoing dialogue with those around us. I’ve loved the times I have shared “Curl” with people who recognized it as having been derived from Kincaid’s “Girl”. And so it definitely has a strong shared existence.

Reading anything interesting these days besides Kincaid? Any thoughts on how your reading inspires your writing?

I’m always reading something interesting. I’ve been loving Rupi Kaur a lot these days. Her Milk & Honey inspires to me to be a truth-teller and to keep singing my song in those moments when I feel most silenced. I also enjoy Anis Mojani – his new book The Pocketknife Bible is an insight into the life a child who’s growing up and learning how to trust himself through painful and complex struggles of identity and belonging. I'm also reading Rising Strong by Brene Brown. I think all these texts inspire me to actually say what I want to say, to not be afraid, and to face life’s fear and pain and beauty through my reading and writing. Especially through poetry.

Your background is of relevance here, so let's talk about that. You were adopted and are multiracial. The closing lines of your poem speak to your "blackness" – race is a recurring them in your poems.

Race comes through a lot, and especially here, as in "the less black you look, the less likely you are to get questioned by the police", or "the straighter your hair, the more likely you are to succeed". I also had some fun in playing with the word “kitchen”, a term that describes the back of your head where the hair is curliest or the hardest to brush. I want to make sure readers don't think that the term is only a metaphor, though it could easily be just that, and I did grow up having my hair braided by a white mother inside our kitchen. When I talk about straightening away your kitchen and your blackness, what I’m really interested in is the decolonizing of that word. I’m calling into question the belief that once you straighten your hair, everything in your world will be right and that people will actually love you. The last couple sentences are what I want to haunt people with: “Let this heat press away your curls, your kitchen, your blackness. Let it warm you like the love you are sure to soon have.” A lot of individuals still buy into that falsehood and it’s been the source of trauma across the black community as a whole. Somehow, having "straight/nice" hair has come to be associated with having a better education and more economic status. To this day it’s hard for me to feel confident about my hair in job interviews because I don't want people to be like “woah, her hair is crazy,” but I also don't want people to be like “whah, your hair is crazy, can I touch it?” (Sarcasm, but for real!) So the poem was actually birthed out of a series of comments made by my black co-workers who were encouraging me to straighten my hair. I must have heard that suggestion at least seven times within a two-week period. And I hear these things from white, black and all people, all the time. I'm not sure which of these is the most hurtful.

A friend and I used to talk a lot about this topic of racial self-hatred – those dealing with it would not frame it as self-hatred per se but self-preservation; as simply "I'm doing whatever I have to do to get a leg up." But that leg up is in the wider context of a culture that won’t embrace you as you are. I keep thinking of James Baldwin: "You’ve got to tell the world how to treat you, because if the world tells you how you are going to be treated, you’re in trouble."

You do a lot of work with teens and in particular with teens who live in poverty. Tell us a little about that.

I’ve been working with inner city youth and vulnerable youth populations for the last six years. I believe God gave me this desire to work with urban youth, and I’ve had incredible opportunities to partner with the most visionary youth I can imagine, all across the country from Chicago to LA to Seattle to Denver, and soon-to-be Flint! I enjoy working with non-profits who value community development and raising up youth with strong, positive identities and self-worth. Currently I’m working on a grant for a project that through a series of art installations promotes positive perceptions of youth of color, a kind of "social advertisement" by youth in the neighborhood of Rainier Beach in Seattle. I’m also doing poetry therapy with students around violence and normalized trauma in their communities due to the war on black bodies, especially on the young. The team I’ve been working with is loosely affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement while also taking it further to create a new movement called "My Life Matters." The purpose of this language is to reinforce these young peoples’ identities, empower them to share their stories, and help them fight injustice in their communities in a real and meaningful way.

No doubt you collect a ton of ideas for your writing by doing this work. Maybe tell us a little about your poetry education – where it’s been, where it’s going. What advice would you offer to poets who are writing poetry on their own?

I started writing songs at a young age, in middle and early high school, as a way of coping with depression. Then in middle school, I wrote an essay for what I thought was just an essay prompt titled " If The Capitol Walls Could Speak". Our seventh grade teacher entered these essays in the Daughters of Revolution essay writing contest and my essay ended up winning locally in the county, state and region. It went on to be one of the top 10 nationally. Then in high school I took a creative writing class and loved it so much I kept writing and eventually had a piece published in Teen Inc my senior year of high school. I didn't know that creative writing was a profession until I was about 20 and took classes at a community college under a few wonderful mentors. I often considered doing social work because I’d worked with urban communities and loved that. But I didn’t want to do work that wasn't creative. So I stuck with poetry and it stuck with me, and I fell in love with it and continue to be awed by it. I studied creative writing and art as an undergrad; now I’m earning my master's in urban studies and community arts. The degree program is based on trauma-informed arts creation, with the purpose of transforming urban and displaced communities into hope havens that are equipped for resiliency. I’m incredibly excited to be using my background in poetry and art in this way.

The advice I have for others is to keep on writing, even when it’s difficult. I recently came out of a season where I was dealing with anxiety and didn't write for almost a year. Now I’m writing quite often. Do whatever it takes to stay inspired: surround yourself with your favorite quotes and books and objects; put stickies on your mirror and in your car or on your bike that remind you of the creative energy you possess and can offer in the future as a gift to others. Get together with friends who are creative and/or passionate about writing and encourage each other to pursue your individual goals. Set strong deadlines; gather over good food and submit to your favorite publications. Celebrate each other’s successes. Read poems together that inspire you to wonder and go outside and adventure and love.

Is there any “homework” you’d like to assign our readers?

I'd like for readers to write a self-portrait poem that is a response to something that is going on in their lives or in the wider world, using this poem as a guide or perhaps a mirror. When writing a self-portrait poem, consider who you most truly are in this instance and dive wholeheartedly into what that means. Strive for simplicity in language and image and see what happens.

Readers can send their poems to me at katelyn.durst[at]gmail.com and I will send readers a poem back of my own self-portrait.

Share a poem you love, and tell us why you love it.

You know, I have to go with this older yet very rich poem that I often return to. It’s "Eating Poetry" by Mark Strand. I love the lines, "There is no happiness like mine, I have been eating poetry." To me this poem is not just about devouring a poem you love and staying in love with that thing. It’s also about the beauty in the process of reading and performing poetry, how it transforms and heals us so that we can become wild and embodied in the way we’re meant to be. When Strand talks about “romping with joy in the bookish dark”, I think about my struggles with anxiety, depression, PTSD. And I think about poetry. It's like when you’re sitting in a theater and someone kills the lights, and for a while you’re sitting in darkness but then the movie begins, with music and people laughing and learning to love, and you realize that you’re not so alone after all.

===

KATELYN DURST is a poet, community artist, creative activist, teacher and youth worker. She has worked within urban youth development and urban community development for ten years in cities such as Chicago, Denver,DC, LA, Seattle and Flint (MI). A current artist-in-residence at Flint Public Art Project, she has taught poetry for six years and conducted poetry therapy workshops at a youth psychiatric hospital and Freedom Schools, a workshop focused on healing from the unjust deaths of youth of color. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Controlled Burn, The Lightkeeper, Deep Fried Poetry, The Offbeat, Teen Ink, New Poetry Magazine and Tayo Literary Magazine. In her spare time, Katelyn rides her bicycle named Ebony Jade, bakes gluten-free pastries, and dreams of her next adventure of becoming an urban beekeeper. She is pursuing a master’s degree in Urban Studies and Community Arts from Eastern University.

Life's Great Lies, Thought Made Flesh, and the Ritual Possibilities of Form: Joseph Fasano on His Poem "Hermitage"

Joseph Fasano

Joseph Fasano

When I initially contacted Joseph Fasano for an interview in late July, I had several poems in mind as possibilities to discuss. But when he suggested "Hermitage" I felt in that choice something of a predestiny; it was the first poem of his I had ever read, and when we had our interview I was reminded what about it had so commanded my attention and drawn me to all of his work: lines of unusual breath and music, cultivated from language of the kind his teacher Mark Strand described as "so forceful and identifiable that you read [these poets] not to verify the meaning or truthfulness of your own experience of the world, but simply to saturate yourself with their particular voices." Rilke's "inner wilderness", twined with Fasano's bracing intelligence, were strongly in evidence throughout this exchange. — HLJ

===

It strikes me that the subject on which this poem turns consists in its final two lines: "the great lie // of your one sweet life", that thing at the poem's opening that was once "too much." The speaker's address to a "you", the reader, seems to presuppose that at one time or another everyone will have to reckon with such a lie in their own lives. So let's begin there and work our way backwards…tell us a little about the great lie that began this piece.

All I know is that it's different for everybody, that great lie. It's a platitude to say that we all lie to ourselves in some way to live. Maybe we tell ourselves things are fine when they're not. Maybe we need to believe they're not fine when they are. In any case, of course it's true that a certain falseness in the way we live might protect us from a radical truth we're not ready for. Maybe we need an actual, practical change in our living situation. Maybe we need a change in our way of seeing things. Whatever the case may be, it's terrifying to face the nakedness of a new truth–or perhaps I should say an old truth, an ancient truth that has been living inside us – especially when we hardly have a language to talk about that truth.

I see this poem as the speaker's way of beginning to saying 'yes' to certain things that he had previously rejected–things perhaps in himself, things perhaps in the world. But what interests me most is the silence after the last line. It's clear to me that the speaker of this poem has yet to find a language in which to say that 'yes,' in which to live it to its fullest. I see the final question as both confident and desperate: What would you have done? What should I do? Everything we say asserts our deepest beliefs, even when we're unaware of those beliefs. But what happens when those beliefs change, radically and even perhaps without our knowing? What steps forward to fill the new silence of our lives then?

===

HERMITAGE

It’s true there were times when it was too much

and I slipped off in the first light or its last hour

and drove up through the crooked way of the valley

and swam out to those ruins on an island.

Blackbirds were the only music in the spruces,

and the stars, as they faded out, offered themselves to me

like glasses of water ringing by the empty linens of the dead.

When Delilah watched the dark hair of her lover

tumble, she did not shatter. When Abraham

relented, he did not relent.

Still, I would tell you of the humbling and the waking.

I would tell you of the wild hours of surrender,

when the river stripped the cove’s stones

from the margin and the blackbirds built

their strict songs in the high

pines, when the great nests swayed the lattice

of the branches, the moon’s brute music

touching them with fire.

And you, there, stranger in the sway

of it, what would you have done

there, in the ruins, when they rose

from you, when the burning wings

ascended, when the old ghosts

shook the music from your branches and the great lie

of your one sweet life was lifted?

Joseph Fasano

Joseph Fasano

When I initially contacted Joseph Fasano for an interview in late July, I had several poems in mind as possibilities to discuss. But when he suggested "Hermitage" I felt in that choice something of a predestiny; it was the first poem of his I had ever read, and when we had our interview I was reminded what about it had so commanded my attention and drawn me to all of his work: lines of unusual breath and music, cultivated from language of the kind his teacher Mark Strand described as "so forceful and identifiable that you read [these poets] not to verify the meaning or truthfulness of your own experience of the world, but simply to saturate yourself with their particular voices." Rilke's "inner wilderness", twined with Fasano's bracing intelligence, were strongly in evidence throughout this exchange. — HLJ

===

It strikes me that the subject on which this poem turns consists in its final two lines: "the great lie // of your one sweet life", that thing at the poem's opening that was once "too much." The speaker's address to a "you", the reader, seems to presuppose that at one time or another everyone will have to reckon with such a lie in their own lives. So let's begin there and work our way backwards…tell us a little about the great lie that began this piece.

All I know is that it's different for everybody, that great lie. It's a platitude to say that we all lie to ourselves in some way to live. Maybe we tell ourselves things are fine when they're not. Maybe we need to believe they're not fine when they are. In any case, of course it's true that a certain falseness in the way we live might protect us from a radical truth we're not ready for. Maybe we need an actual, practical change in our living situation. Maybe we need a change in our way of seeing things. Whatever the case may be, it's terrifying to face the nakedness of a new truth–or perhaps I should say an old truth, an ancient truth that has been living inside us – especially when we hardly have a language to talk about that truth.